We argue the Australia’s renewed terms of trade boom since 2016 has been an important factor behind both Australia’s weak productivity growth and a creeping lack of fiscal discipline.

Very high commodity prices and the terms of trade are Australia’s Achilles heel.

But forecasting the terms of trade has been a mug’s game for a long time. Even significant weakness in China’s steel-hungry property sector has hardly dented Australia’s terms of trade.

If, and when, the terms of trade do decline, it is clear to us that this will spur much faster productivity growth than what has been the norm recently in Australia.

The problem is that the ensuing weakness in national income would be the primary issue. And governments would be under pressure to curtail spending against an unfamiliar backdrop of downside revenue surprises, making the economic pain worse.

For now, it’s in the risk bucket. Fingers crossed.

The first part of this piece takes a high-level look at developments in Australia’s terms of trade, labour productivity and government spending.

The second part looks at fluctuations in labour productivity trends through an industry lens - mining vs non-mining - since the early 2000s.

Finally, we show that weak labour productivity growth in recent years has been accompanied by weak growth in real (producer) wages. We argue that this has helped to sustain resilient employment growth.

There is a growing risk, however, that many firms are quickly turning to a focus on costs, with private labour cost growth already slowing noticeably. Employment could be more clearly next in the firing line, particularly outside government-supported industries.

Terms of trade boom 2.0

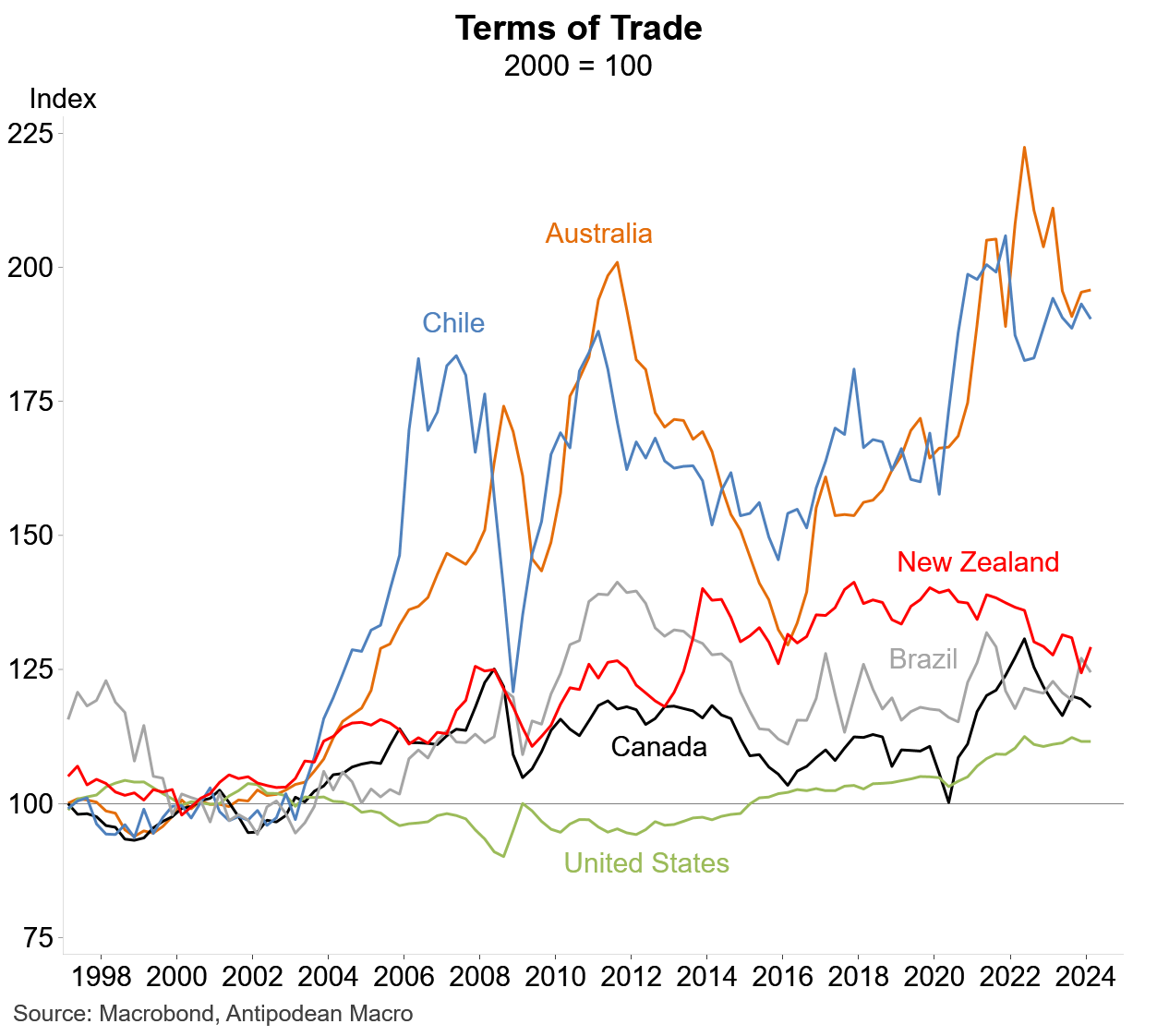

Australia’s terms of trade - the ratio of export to import prices - is again at a very high level, boosted by high commodity prices. Only Chile matches Australia’s terms of trade boom since the early 2000s.

While Australia’s terms of trade has declined from the record high reached in 2022, it remains close to the previous peak set in 2011 which resulted from China’s massive stimulus in response to the Global Financial Crisis. As the effects of that stimulus waned, so did prices for Australia’s key commodity exports and terms of trade for several years thereafter.

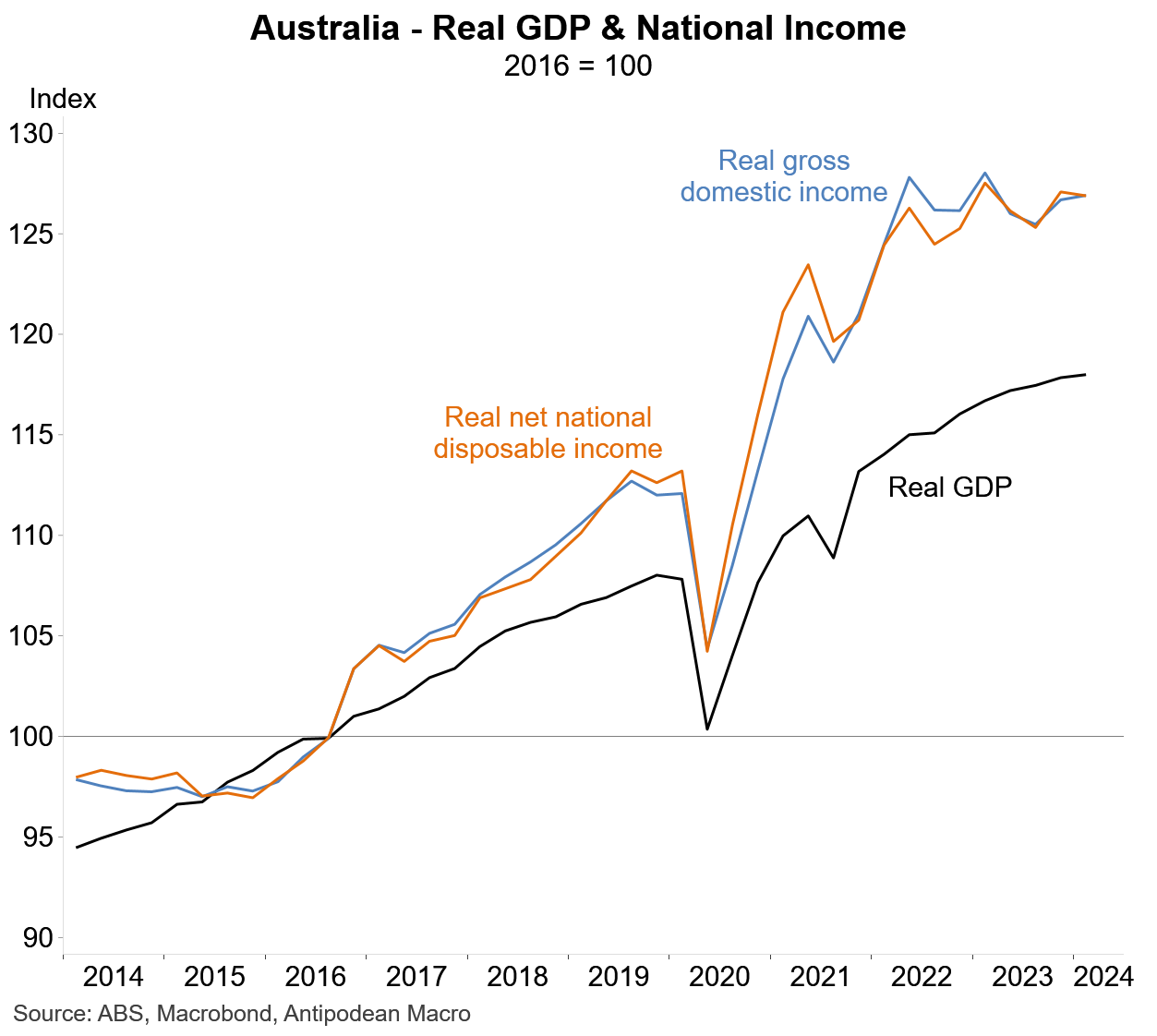

Why does this matter? A high terms of trade increases a country’s collective purchasing power. Measures of Australia’s real national income - as opposed to real GDP - have again benefited from the significant increase in the terms of trade, rising 27% since 2016 compared with just 18% for real GDP.

Disincentivising productivity gains and fiscal discipline

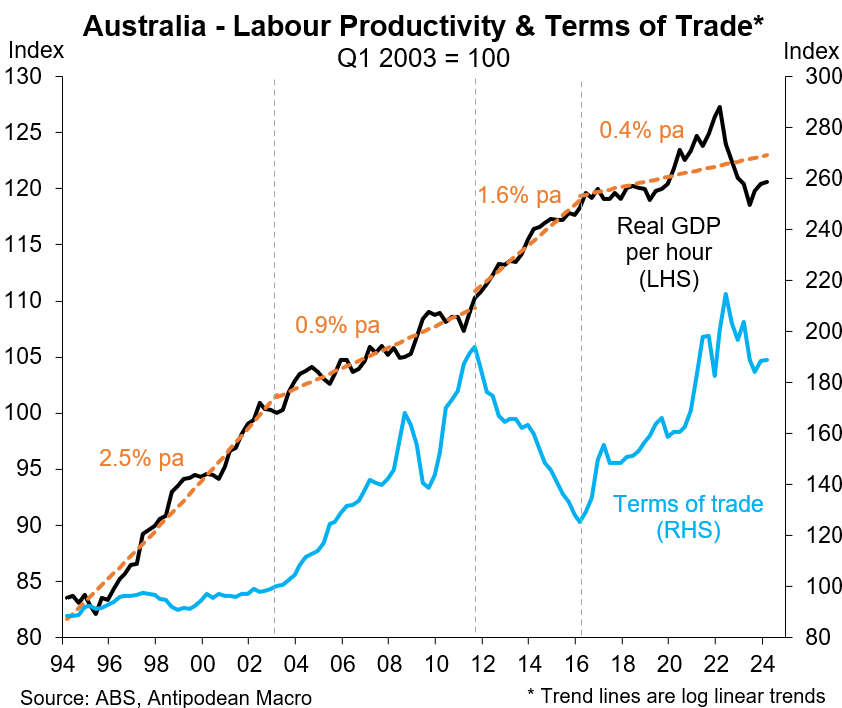

Like the initial ‘free kick’ to Australia’s real income from 2003 to 2011, the more recent terms of trade boom has again been accompanied by a slowing in Australia’s productivity growth and looser fiscal settings.

While there are many other reasons why productivity growth has slowed in Australia and globally, it is clear in our view that Australian businesses - including in the non-mining sector - have not been strongly incentivised to strive for efficiency gains because of relatively strong growth in income.

The 2003-11 terms of trade boom coincided with a sharp slowing in Australia’s labour productivity growth to under 1% per annum, on average. Amid the decline in the terms of trade from 2011 to 2016, average annual productivity growth again strengthened to 1.6%. Since then, productivity growth has weakened significantly alongside the surge in the terms of trade.

Comparing the paths for labour productivity and terms of trade between Australia and the United States is striking.